Structured products often sit in a grey area of investing. They are frequently marketed as smart solutions that combine protection and performance, especially in uncertain markets. At the same time, many retail investors avoid them altogether because they seem complex, opaque, or “too engineered to be trusted.”

The truth, as usual, sits in the middle. Structured products are neither magic tools nor financial traps by default. They are instruments with specific mechanics, specific goals, and very specific risks. Understanding how they work is essential before deciding whether they deserve a place in your portfolio.

What Are Structured Products, in Simple Terms?

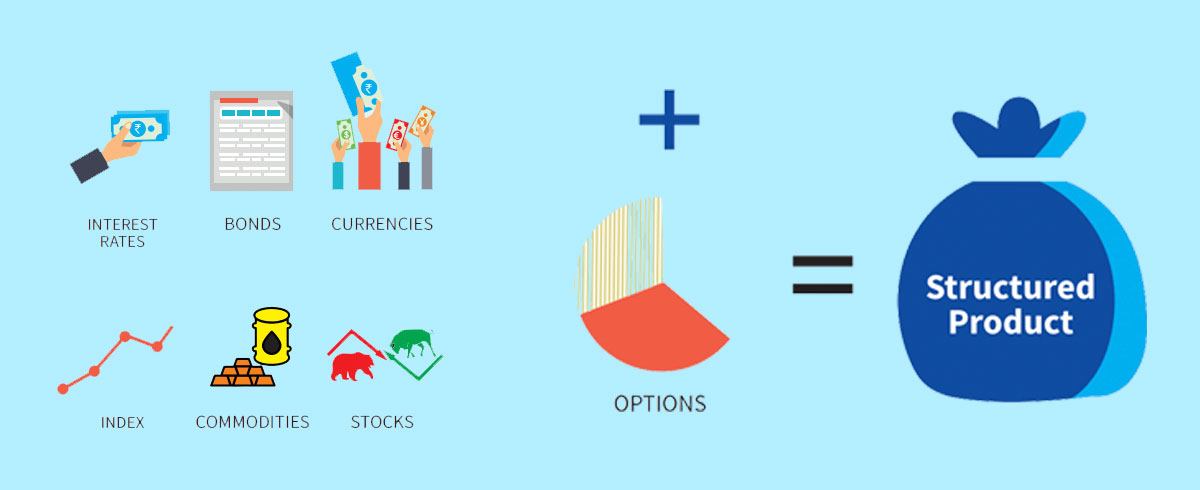

A structured product is a financial instrument created by combining traditional assets—typically bonds and derivatives—into a single investment. The goal is to shape the return profile in a very precise way.

Instead of simply buying a stock or a bond, you’re buying a pre-packaged payoff structure. That structure might aim to protect part of your capital, generate enhanced income, or provide conditional exposure to an underlying asset such as an equity index, a basket of stocks, or interest rates.

This engineering flexibility is what makes structured products attractive—and what makes them complex.

Capital Protection: What It Really Means

One of the most appealing features of structured products is so-called capital protection. In theory, these products promise to return some or all of your initial investment at maturity, regardless of how markets perform.

In practice, capital protection usually comes from allocating part of your investment to a bond that matures at par, while the remaining portion is used to buy options linked to the underlying asset.

However, “capital protected” does not always mean risk-free. Protection often depends on:

- holding the product until maturity

- the creditworthiness of the issuing bank

- specific market conditions

If the issuer defaults, protection may vanish entirely. During the 2008 financial crisis, investors learned this lesson the hard way when several “protected” products failed due to issuer risk.

Yield Enhancement: Why Returns Can Look Attractive

Another common goal of structured products is yield enhancement. In a low or volatile interest-rate environment, these products can offer coupons that look far more attractive than traditional bonds.

This higher yield usually comes from selling options—often on equity indices or stocks. In exchange for giving up some upside or accepting conditional risk, investors receive regular income.

For example, some yield-enhancing products can offer annualized coupons between 6% and 10%, depending on market conditions. That sounds appealing—but the yield is rarely guaranteed.

In many cases, the income depends on the underlying asset staying above a certain level. If markets fall sharply, coupons may be reduced or skipped entirely.

The Trade-Off You’re Always Making

Structured products always involve trade-offs. You might gain downside protection but sacrifice upside potential. You might earn higher income but accept complex conditions or hidden risks.

This is why they are often described as “designed outcomes” investments. You’re not betting on markets in general—you’re betting that markets behave within a specific range.

If markets move outside that range, the product may underperform significantly.

Understanding the Risks Beneath the Surface

The biggest risk of structured products isn’t volatility—it’s misunderstanding.

One major risk is issuer risk. Unlike ETFs or funds that hold segregated assets, structured products are debt obligations of the issuing institution. If the issuer fails, investors become creditors.

Another risk is liquidity. Many structured products are not easily tradable before maturity. Selling early can result in losses, even if the underlying assets have performed well.

There is also complexity risk. Payoff structures can be difficult to fully understand, making it harder to evaluate performance or compare alternatives. Studies show that retail investors often misjudge the risk-return profile of structured products, especially under stress scenarios.

Are Structured Products Suitable for Retail Investors?

Structured products are not inherently bad—but they are not universally suitable.

They may make sense for investors who:

- fully understand the payoff structure

- can hold the product until maturity

- accept issuer and liquidity risk

- use them as a small, complementary allocation

They are generally less suitable for beginners, investors seeking simplicity, or those who need flexibility and transparency.

According to European market data, structured products typically work best as satellite investments, not as portfolio foundations.

Structured Products vs. Simpler Alternatives

Many of the goals addressed by structured products—income generation, downside protection, volatility management—can also be achieved using simpler tools such as diversified ETFs, bonds, or option-based strategies with more transparency.

The key difference is control. With structured products, control is delegated to the product design. With simpler instruments, control stays with the investor.

In the long run, simplicity often improves decision-making and reduces costly mistakes.

How to Evaluate a Structured Product Before Investing

Before investing, it’s crucial to understand:

- how returns are generated

- what happens in worst-case scenarios

- who bears the credit risk

- how and when you can exit

If these questions can’t be answered clearly, the product may not be appropriate for your portfolio—regardless of how attractive the brochure looks.

Using Structured Products Wisely

When used correctly, structured products can serve a specific purpose: enhancing yield in sideways markets, limiting downside risk, or tailoring exposure to particular scenarios.

When misunderstood, they can introduce unexpected losses, frustration, and disappointment.

The difference lies entirely in education and expectation management.

Complexity Is Not a Substitute for Strategy

Structured products are tools—not shortcuts. They require a clear understanding of risk, discipline, and realistic expectations.

For most retail investors, long-term wealth is still best built on diversification, consistency, and simplicity. Structured products may have a role, but only as part of a broader, well-thought-out strategy.

In investing, complexity should always serve a purpose. If it doesn’t, it’s usually a warning sign—not an opportunity.